I knew that curry could connect me even deeper to the people I know and love. I didn’t know it could connect me with the grandfather I can’t remember meeting.

Just over a year ago, we moved as a family from the New Forest to Salisbury. The physical distance is only 12 miles – but in every other sense, it was a big move. We were leaving the small-holding where we’d lived for 14 years, and kept cattle, pigs, geese and chickens. For some of those years, we were virtually self-sufficient in meat (and I’ll blog about that soon).

The garden at our new home in Salisbury might be smaller than the fruit-cage in the New Forest where we grew our raspberries – but we love the house, the street, the weekly market and the city.

And we love our neighbours – who said hello on the first chaotic day of packing cases, gave us parking slips – and have since taken us on walks to parts of the city we didn’t know, fed our cats when we were away, and sent over teenage children to fix IT issues. The stuff of modern life.

One of the phrases we kept on hearing from neighbours in the early weeks was: “You must meet your namesakes in this street… the Baines”. My wife Sue asked me several times if she thought we could be related to this other family – and I answered that I’d never met someone with our name and found a family connection.

After a couple of weeks, our new neighbours invited us to dinner. The distance from our house to theirs is about 30 feet, and every day we’d admired its carved Elizabethan exterior.

I rang the bell, the door opened – and in front of me stood a man looking exactly like my father. If he saw astonishment in my face, he didn’t show it.

Sue and I looked at each other. The man resembled my Dad in every way – even more closely than my uncle.

I lost my Dad over two years ago. I suppose my visual memory of him is fading. But the man walking us through his house didn’t simply look like my father – but shared the same mannerisms, the same gentleness.

Our new neighbours served us drinks. Chatting about careers, our host said that after retiring from the army, he’d worked for a government department (which I knew my father had also worked in).

“Did you work with Richard Baines, my Dad?” I asked.

“Oh yes, cousin Richard.”

And suddenly my world has just got bigger. A neighbour has morphed into a blood relation – and the wisdom I thought I’d lost in my Dad is alive and well on the other side of our street.

Some months later, we invited the Baines to our house – for a curry. They’d lived and worked abroad a lot – described India as their favourite country – and we wanted to cook them something memorable.

For the chutneys, I went back to almost the first ever Indian recipe book I ever cooked from: Food of India by Murdoch Books. The mint and coriander chutney – along with the date and tamarind chutney – are two of the best I know. I never tire of cooking them.

For the starter, I went back to the same book, and the street food classic of Kashmiri lamb chops. If you’re looking for a dish you can prepare the night before (in a ginger and chili marinade) and cook in four minutes on the day – this it.

For the main course, we cooked Sea bass with a green spice crust from Atul Kochhar’s Fish Indian Style. Faced with the infinity of Indian cookbooks, I don’t often do a recipe twice (so many curries, so little time) but this is a classic I come back to often. Simple to cook, and super-sophisticated on the fork.

And in the shared glow that a meal somehow creates, it occurred to me there was a book which the Baines could help me understand: my grandfather’s photo album.

Given to me by Dad some years back, the album is a thick, black cloth-bound book – filled with photos from my Grandfather’s youth. Almost every image is of school sport – sprinters breasting the tape; end-of-season team portraits.

Until this moment, the black-and-white (and often strikingly formal) photos had seemed remote from me – like a language you struggle to understand.

But in the Baines’ hands, the images suddenly came to life.

Turning the pages, and reading the dates hand-written in white ink, my neighbour calculated that his father and my grand-father were exact contemporaries – both born in the last decade of the 19th century.

Starting with a photo taken in 1903, my grandfather’s album follows him through every school and every sports team. Cricket, football, hockey. Press cuttings with scores from the matches are pasted on pages opposite. The faces in front of us mature from young children, to boys, to men.

It’s the story of Edwardian youth.

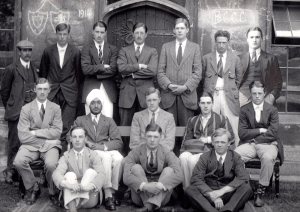

Then the date gets to 1914, my grandfather’s goes to university, pastes in a photograph of the college cricket team in his first year (see the picture at the top of the blog – my Grandfather seated on the bench, centre)

– and the album falls off a cliff.

The Great War has started.

My neighbour’s father volunteers at the age of 17; my grandfather at the age of 20.

“It’s incredible they both made it back alive,” says my neighbour, “so many didn’t.”

Over 700,000 British soldiers died in WWI – the bloodiest in the country’s history.

And suddenly the young faces on the pages look at me from the page in a different way. Almost all would serve in the war; more than one in ten would die in combat.

Both men in our families survived. My grandfather went back to university to finish his degree.

But the album stops in its tracks in 1914 – along with the Edwardian world that vanished with it.

After dozens of pages of sporting camaraderie, the final image in the book is my grandfather sitting with his new regiment. Drawing on his own military career, my neighbour points out details from the photo: my grandfather’s rank, his regiment, the fact that all the men are wearing breeches – meaning the future campaign would take place in Asia.

And then nothing.

Blank page after blank page. The Great War has started, and the pictures stop.

We talk, briefly, about the two men’s experience of the war: details too personal to share.

Long into the night, after our guests have gone home, I read and re-read the notes in the album. My grandfather feels closer to me than at any point in my life.

All thanks to our new neighbours – and to the timeless alchemy of a shared meal.

What a beautiful story. I recently digitised my mother’s 50’ish photo albums, many from her youth on a farm and pre-marriage times working in the Australian Outback in the 1940s. looking at the 5x5cm photos large on the screen brought them to life with details we never noticed before. I know how you felt. A connection with someone no longer here